I have a particular knack for romanticizing things from the past—even the clunky, nasty bits—like do you ever get emotional imagining what it was like to promote events before the internet? I do.

The internet has a gift for making everything feel static and sterile and formulaic. It’s always changing because people are always adding to it, but the things you upload into its abstract body of nothingness stay put, dry up, and lose meaning, like dead leaves decomposing at the bottom of a pile.

Nothing lasts forever, but the internet attempts to preserve indefinitely. It’s a spooky ambition. The longer something lives online, the further it travels, the less human it feels. Where are the people who made the internet? It ate them long ago.

A paper poster is disposable, which is as it should be. There’s an urgency to paper, and a level of commitment that doesn’t come through online. The message will self-destruct—or fade in the sun or disintegrate in the rain or be ripped down by a barista after the date has passed—so pay attention. When you see a poster, you know in your heart that someone created it, printed it, taped it to the wall. You can visualize the steps, you can sense the devotion.

If and when that person uploads the same exact design to the internet, it travels farther but it says less. The gesture of an upload takes infinitely less time, thought, and energy than analog marketing, which requires not only the printing and the travel but an awareness of in-person community that informs where in the city a poster should go. Flyering relies on people showing up to places in person with open hearts and curious eyes.

I wondered, back in 2021, what would happen if I took a phones-down, eyes-up approach to promoting an event. In other words, if I put together a show but didn’t post about it online would people still come?

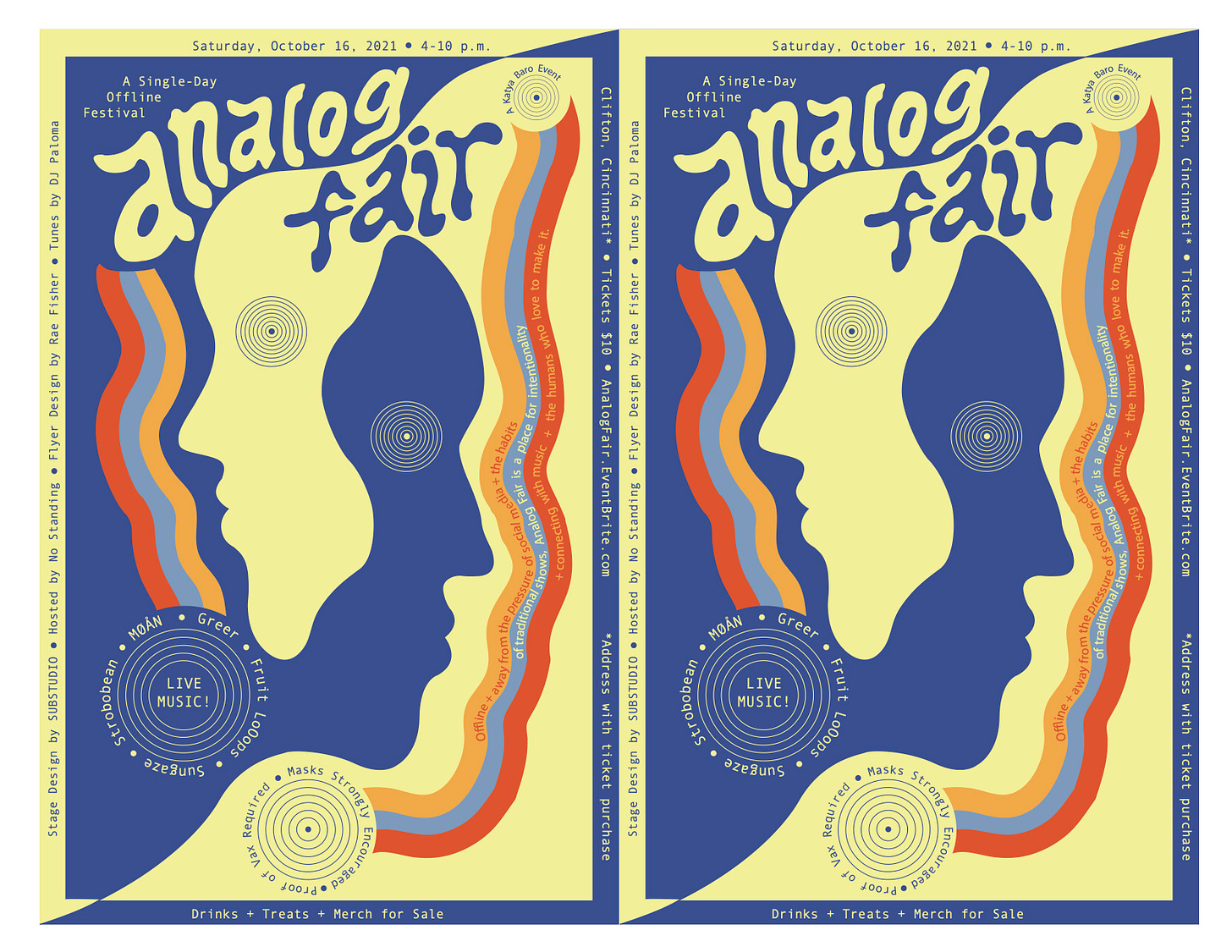

My friend Megyn has a stunning back yard with the remnants of an old structure that works well as a stage. That spring she invited me to organize a show there. Since it wouldn’t quite be public anyway, this seemed to be the perfect opportunity for an experiment. I dubbed the event Analog Fair. I booked some bands, my friend Rae designed a handbill, and we distributed them to friends and friends of friends all over the city. Each band agreed to make no mention of it online.

About 50 people showed up that night, flashing their vaccination cards at the door like IDs to get inside. There was a bar beneath a tree where another friend served beers and a signature cocktail, and a rack of vintage clothing for sale. I set up a green room in Megyn’s garage where I served chili and fixings to the performers. A few volunteer photographers documented the night with film photos as bands played in front of a diaphanous, backlit structure designed by my friend Ingrid using old awning frames. It was really beautiful.

I’m grateful for the venues in my city where bands can play and sometimes get paid. Booking a bar show and posting online is a formula that can work. But I’m infinitely more inspired by any opportunity to break the formula and create a new approach. Through my first year producing Analog Fair, I learned it wasn’t just the posting online that had lost my interest, but the settings and the general production as well. I’m no longer excited by black rooms with floors sticky from sloshed draft beer. I want settings to be a forethought, and events that prioritize novelty and curiosity over drink sales. I’m seeing more of this in Cincinnati and it pleases me. In a few weeks an event called North by Northside will include live music in coffee shop courtyards and classic diners, and next month my friend Nick will put on a generator show at the edge of the Ohio River.

In 2023, I did Analog Fair Volume II. With the help of local sponsors, I raised enough to book an old woodworking factory (now mostly used as a wedding venue) and to hire local and regional acts from five different cities. Ingrid, now a professor at University of Kentucky, had her students design and install a new stage backdrop which blew in the breeze behind performers. As a nod to the analog of it all, there were vendors with zines and zine making, tarot readings, button making, and more. Acclaimed photographer (and friend of the fam) Michael Wilson came and took large-format film portraits.

That year, the anti-internet stance got a little stickier. Artists felt more at a loss for how to bring people out if they couldn’t post online. They were, at some points, irritated at the request to avoid social media. Maybe in the heart of the pandemic people were more willing to try something new, or maybe it’s just too ridiculous to keep a public event offline in the 2020s.

I realized if I wanted people to understand what the event was, I had to let the internet play a part. Otherwise, I was asking people to change their lifestyle just to tune into one event. Not fair! I made a website where people could buy tickets and learn more.

That year, about 200 people showed up, having learned about the festival primarily through fliers, handbills, word of mouth, and local media. It was way more work than I imagined (as I am infamously bad at estimating time and energy requirements) but when it was over—when Glacci was wrapping up his set and the rain that held off all day started to sprinkle—I was glowing. Still, I thought, I’ll never do this again.

And yet, here we are on the eve of Analog Fair Volume III. (I’m so excitable I can talk myself into anything.) Doors open tomorrow at 4 p.m. at PAR-Projects, an artist-led organization in Cincinnati, Ohio. There will be local bands, solo performers, shadow puppets, comedy, tintype portraits, live paintings, a vinyl DJ, and a lively MC in a pink suit. Tonight, we kick things off with with a poetry reading and a Mary Oliver summoning workshop at 7 p.m. at Conveyor Belt Books in Covington, Kentucky. (You’ll have to show up if you want to know what it means to summon Miss Mary.) If you’re in Southwest Ohio I hope you’ll come by! Tickets are online, or you can buy them in person at the reading tonight.

I’m confident this year’s Analog Fair is the most sensible yet. With the help of some logical thinkers and collaborators I’ve reigned in my big, dreamy notions so they can fit better into this world. (Shout out to co-producer Lillian Currens, plus Eric Blyth, Nick Keeling, and the others who have lent time and energy and thought along the way.) Now people are welcome to post online however they please—but the festival itself does not use social media. An early call to artists introduced us to both established and up-and-coming creatives outside of our bubble and helped root the programming in the local community. Vendors will be near the stage rather than off to the side so they’ll get more foot traffic. And the language around the festival’s mission and ethos is, I think, clearer than ever.

Analog Fair is a music, arts, and literary festival that celebrates creative and analog practices. Conceived from a place of curiosity and experimentation, Analog Fair started as an “offline” festival. No social media, no online presence. While we aren’t anti-phone, our goal is to bring artists, creatives, and makers face-to-face. During a time where creating these bonds is absolutely vital to our survival, Analog Fair makes space to slow down, and cultivate something deeper and more resilient. We invite you to put away your phone, engage the senses, and bring mindful focus to the arts and people around you.

Will I do it again? Time will tell. Will it happen tomorrow? Helllll yeah. See you there!